The Des Moines school knew no one would be able to do it justice, not after it had been worn by Johnny Bright, whose story is one of the most glorious, the most gut-wrenching…and ultimately the most gallant that college football ever has known.

Midway through the 1951 season Bright may well have been the best athlete in all of college sports and he certainly was on the football field.

In the two years previous, he’d set the NCAA record for total yards in a season and five games into that 1951 campaign – his senior season – he was leading the NCAA in rushing yards and was the front-runner for the Heisman Trophy, an accomplishment that would have made him the first African American ever to be given the preeminent award.

He’d been dominant in basketball and track as well but had given up those pursuits to concentrate on football, where – as a dual threat quarterback like Lamar Jackson and Patrick Mahomes are now – he’d captured the imagination not only of other Iowans, but much of the nation the way another Des Moines athlete did recently.

Long before there was Caitlin Clark, there was Johnny Bright.

But then came the October 20, 1951 match-up with Oklahoma A&M – which is now Oklahoma State University – in Stillwater, Oklahoma.

It became one of the most infamous games in college football history when Bright became the victim of a racially-motivated assault, hatched, many say, by A&M coaches and carried out in thuggish fashion by one of the Aggies’ defensive linemen.

While there had been incidents in other games involving brutal cheap shots of African American players in those Jim Crow days, most went unreported by the white press and unpunished by the game’s governing bodies.

This incident was different.

In the days leading up to the game, it was reported that new A&M coach J.B. Whitworth had urged his players during practices to “get that (n-word)!”

Both the local newspaper and the A&M student newspaper published accounts that Bright was a targeted man. And in the stands that Saturday, Bright saw a sign with the same boldly painted three-word directive that the A&M coach had hammered home to his players:

“Get that (n-word)!”

Those unsettling underpinnings – coupled with the fact that Drake was 5-0 and on the cusp of claiming the Missouri Valley Conference title – were enough for the Des Moines Register to fly two photographers, John Robinson and Don Ultang, to Stillwater to shoot pictures for the next day’s newspaper.

Because of the tight deadline, the pair only would be able to stay for 15 minutes of the game and then would have to rush back to Des Moines to get the images into the Sunday edition.

As it turns out, they didn’t need that much time.

On the very first play from scrimmage, Bright – in the days before helmets required face masks – was standing away from the action after he’d handed the ball off to his running back and was sucker punched by Aggies’ defender, No. 72, Wilbanks Smith.

The blow, which the 205-pound Smith amplified by leaping off the ground to gain full impact, broke Bright’s jaw.

Twice more in those opening minutes – once after throwing a 61-yard touchdown pass – the injured Bright was knocked unconscious by away-from-the-action or after-the-play assaults.

One of those attacks was perpetrated by Smith, as well.

In need of medical attention, a reluctant Bright finally was led off the field. While Oklahoma doctors did examine him, he was not admitted to a hospital and was told to wait until he was back in Iowa to get his jaw wired shut.

In the Stillwater train depot, it was reported Bright was told he couldn’t sit with his teammates and should move to the “Colored” waiting area.

He refused and his teammates backed him up.

But the Bulldogs, who’d been leading when Bright left the field, had lost the game and the celebrated quarterback’s hope of a Heisman had been crushed, too.

Yet, unlike other race-tainted incidents of the time, this on-field foulness wasn’t overlooked.

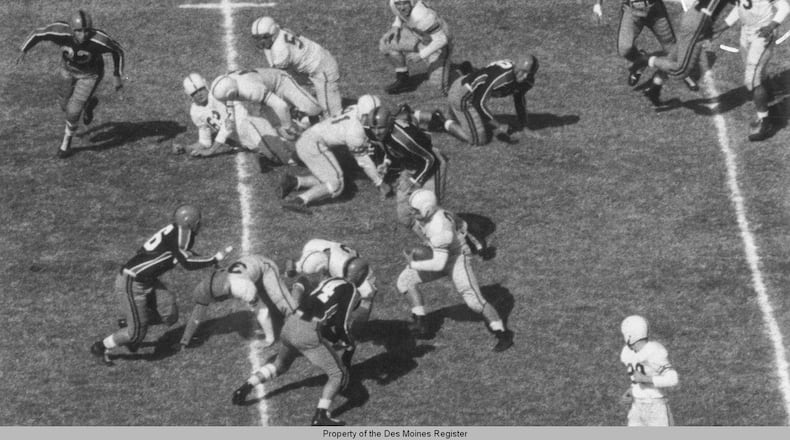

From the opening kickoff, Robinson and Ultang trained their cameras on Bright and ended up recording a six-photo sequence of the ongoing muggings and captured Smith’s jaw-breaking punch.

The photos ran across the sports page of Sunday’s Des Moines Register. They were picked up by newspapers across the country, were published in the popular magazines, Look and Life, and in 1952 they won the Pulitzer Prize.

The attack became known as The Johnny Bright Incident, but Wilbanks Smith’s unrepentant nefariousness is not the part of the story that resonates the most 74 years later.

Even though game officials never dropped a penalty flag and the cowardly Missouri Valley Conference never meted out any reprimand, some good did come out of the incident and it will be in evidence in Saturday’s Drake-Dayton game.

Face masks became required attachments to helmets and penalties and suspensions were enforced for such attacks on players.

But more than that, the post-assault actions of Bright – who went on to be a much-celebrated pro player; a respected teacher, school administrator and youth coach; and a beloved family man – are lessons we all need to embrace in these polarizing, retrograde times.

All of this and so much more is captured in a compelling documentary – “The Bright Path: The Johnny Bright Story” – that is being presented at noon on Nov. 21 at Sinclair Community College.

Free and open to the public, it’s being shown in Building 11, Room 324, in collaboration with the newly-dedicated “Michael and Debbie Carter Center for American History: Our American Journey.”

Michael Carter grew up in Springfield, graduated from Wittenberg University, got his master’s at Wright State, was a former high school basketball coach at Springfield South and Trotwood-Madison, and for a long time has been senior advisor to the president at Sinclair Community College.

With the help of his wife Debbie and his brother, Darnell, a well-known Springfield attorney and educator, he’s compiled an impressive collection of black history information, memorabilia and insight.

Seeing the permanent exhibit – free and open to the public in a newly-designed space whose grand opening was just three weeks ago – is like a visit to a fascinating museum.

The sports section includes an account of The Johnny Bright Incident and copies of Pulitzer Prize winning photos.

In explaining the intent of the exhibits, Carter pointed to black churches who he said have four components:

“You have praise and worship; prayer; preaching the word; and you have testimony.

“These spaces are our testimony.

“They’re not about bearing grievances. They’re about telling the truth of our story. They’re about saying ‘despite everything that’s happened, we’re here. We’re going to make it. And in some situations, we’re thriving.’”

And no one exemplified that more than Johnny Bright.

An unprecedented decision

He grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana and won state wide acclaim in football, basketball and track at Central High.

When he graduated in 1948, Notre Dame was not yet taking black football players and Purdue made him no offer. He ended up at Drake, which had an all-inclusive reputation.

Freshmen were ineligible for varsity then, and as a sophomore, he didn’t start the first game. But once on the field, he ran for two touchdowns, passed for another and amassed 250 yards.

He quickly became a Bulldogs’ starter and ended the season passing for 975 yards and running for another 975. His 1,950 total yards made him the first-ever sophomore to lead the NCAA in that category.

That 1949 season the Bulldogs played A&M in Stillwater, but Bright still was under the national radar, and no incidents of note occurred.

As a junior he upped his offense to 2,400 yards (1,232 rushing, 1,168 passing) and set a new NCAA record.

By then his popularity was sweeping across Iowa.

During the summer before his senior season, he played slow-pitch softball with an all-black team and, as author and historian Mike Chapman noted, some 2,000 people showed up one night to watch him play.

The evening before the 1951 season opener, the Iowa governor and the Des Moines mayor held a Johnny Bright Night on campus and another 2,000 people came and gave their favorite son a rousing ovation.

Through the first five games that senior season Bright already had compiled 2,170 yards and again led the NCAA.

After the assault – with his jaw wired shut and relegated to a liquid diet – Bright pushed to be allowed to play . He missed two games, but returned for the season finale and, with a specially-made Wilson helmet equipped with a facemask, he threw for two touchdowns and ran for another.

Although he won All-American honors, he finished fifth in the Heisman voting.

When Oklahoma A&M refused to acknowledge the assault – the school offered no official apology nor did it reprimand Wilbanks Smith – and the Missouri Valley Conference did nothing either, Drake withdrew from the league.

Bradley University, noting the egregiousness of the act and the lack of response, exited as well.

After A&M joined the Big Eight in 1958, Drake returned to the MVC, but in 1986 the Bulldogs became a non-scholarship program and five years later became an inaugural member of the Pioneer Football League, as did Dayton.

Bradley disbanded its football program in 1970.

As for Bright, he was chosen in the first round of the 1952 NFL Draft – the overall No. 5 pick – by the Philadelphia Eagles and would have become the organization’s first black player.

The roster contained a lot of Southern-born players and Bright wondered what his reception would be. When the Calgary Stampeders in the Canadian Football League offered him $5,000 more a year than did the Eagles, he made the unprecedented decision to bypass the NFL for the CFL.

He became a hero in Canada, playing three seasons with Calgary and 10 with the Edmonton Eskimos. His teams won three Grey Cups; he led the league in rushing four times; and in 1959 he was named the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player.

He was inducted into the CFL Hall of Fame in 1970 and was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame here in the U.S. 14 years later.

While playing pro ball, he got his master’s degree in education at Indiana University and, as the documentary details, he eventually became a much-beloved teacher and coach in Canada.

In 1983 Bright died of a massive heart attack during an elective knee surgery. Just 53, he was buried in Edmonton and left a wife and four children.

It wasn’t until 2005 – 22 years after his death and more than a half-century after the assault – that the Oklahoma State president, at the request of his Drake counterpart, officially acknowledged the incident and apologized.

More than football

As they were growing up, Michael Carter – who’s seven years younger than Darnell – said he’d listen intently to his older brother’s stories in the bedroom they shared before falling asleep.

Nothing changed years later when Darnell went to Drake University Law School and soon shared the Johnny Bright story with him.

Michael was fascinated and delved into the story the way he did so many other tales of African American life in America.

All of that became part of his large collection that he first displayed in a room outside the Sinclair library four years ago.

Sinclair president Dr. Steven L. Johnson was moved when he saw the collection and urged him to make the exhibit permanent. Recently it was moved to an expanse in Building 11.

You can visit the Carter Center on your own or Michael will give you a tour and share stories on myriad subjects. When it comes to Bright, he’ll tell you how Drake named its football field after him and how, in 2020, the university opened its two-year John Dee Bright College.

In Canada another school was named after Bright.

While many things have been done to celebrate Bright, what’s most important is what he did for the rest of us.

Dedicated to developing and mentoring children, he refused to let an ugly incident from the past – and any bitterness it could have fostered now – to detour him down a path that led away from who he really was.

In the documentary, William Rhoden – once a college football player himself who’s had a long career as sports journalist, author and keen-eyed chronicler of the times – put it best:

“Johnny Bright’s story just needs to be told and retold.

“He’s like that rose that grows up through concrete and you’re like, ‘How the hell did that happen?’

“His story is about more than football. It’s about all black folks. It’s about not letting other people’s hatred define you. It’s about feeding off that hatred to flourish.

“Johnny Bright won because he didn’t give that hate any energy. Hate does not win; love does.”

Bright showed resilience and courage and a love of his fellow man and that’s why no one from Drake will be wearing No. 43 next Saturday.

Nobody could fill out that jersey the way Johnny Bright did so long ago and, with the retelling of his story, still does today.

About the Author