William Elias Stepp was involved in nearly 50 criminal cases over a 30-year period. He spent little time in jail. Among the reasons were “forgetful” witnesses, missing evidence, and prosecution missteps.

Haller and others believe Stepp was protected by the FBI and others because he was an informant. He clearly had connections with law enforcement. A raid of his home found confidential police files about himself from the Dayton Police Department.

Former Dayton Police Lt. Daniel Baker told the Dayton Daily News in June 1985 that an FBI agent had been using a prostitute-informant, who had worked for Stepp for years. Stepp had used her to get information on the police, secret service, ATF (Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms), FBI intelligence and the police organized crime unit.

In 1966, then-Ohio Attorney General (and later U.S. Senator) William B. Saxbe proclaimed “the notorious Stepp gang” was responsible for crimes including extortion, burglary and larceny. Several Stepp associates went to prison, but not him.

Stepp was critically wounded in 1963 when he was shot by a farmer who accused him of pistol-whipping his adult son. And in 1969, the Dayton Daily News reported that Stepp had a contract out for him after being blamed for an armed holdup of a card game in Covington, KY.

Stepp kept a lower profile in the 1970s, focusing on his love of auto racing. His cars — often emblazoned with “Billy the Kid” — won multiple titles, and he was inducted in the National Hot Rod Association’s Hall of Fame in 1982. He was also involved in dog fighting in the 1980s, according to related criminal charges he faced.

Stepp home raided

Stepp’s house on Winterhaven Avenue in Harrison Twp. was raided in March, 1984. More that a dozen federal agents using dogs from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base trained to sniff out drugs were at the scene.

The FBI lost 78 of the 129 items taken in the raid.

FBI Special Agent John Heck claimed the seized items “had to have been left behind” because the items had been secured in the Dayton federal building after the 13-hour search by 15 agents and were missing the next day.

Haller was skeptical about how the Stepp evidence was lost.

“You can’t get rid of evidence, it’s a federal violation,” Haller said. “But you can damn sure lose it.”

Troy attorney Jose M. Lopez, who was a Montgomery County special prosecutor at the time, suggested another explanation.

“They didn’t lose that evidence,” Lopez insisted. “I used to tell people all the time it was like what was going on in Boston with Whitey Bulger. Some FBI agents were using Stepp as a snitch and there was another group of agents who were trying to convict him. So, when they did that search, the agents who were trying to use him as a snitch, they seized the friggin’ evidence and everybody forgot, and they walked away from it. I am convinced to this day that is what happened.”

Seized items included $508,000 in a grey suitcase in the attic, $50,020 in a Gucci designer bag, $2,650 in a woman’s boot.

Items lost included “four wax paper envelopes containing white powdery substance,” brass knuckles, three handguns, assorted papers concerning dealings with a munitions plant in Dominican Republic and telephone-bugging-alert devices.

This is when agents found Stepp had confidential police records.

In 1985 a U.S. District Judge ruled that Stepp would not get back $558,110 of the amount seized, ordering it be forfeited to the federal government. Prosecutors claimed the money was related to drug sales.

Lopez recently likened the era to the “Wild West.”

“Jesus!” Lopez said, noting he reached a point to where nothing Stepp got away with surprised him. “At one time they (FBI) hit his (Stepp’s) house and found $560,000 in cash stashed on his second floor and in his bathroom. Money was flowing.”

‘Snitch’

Nothing in Stepp’s long criminal career more highlighted his power to evade prosecution than the case of an FBI informant who said she paid him $225,000 to obtain and destroy evidence in her own criminal case.

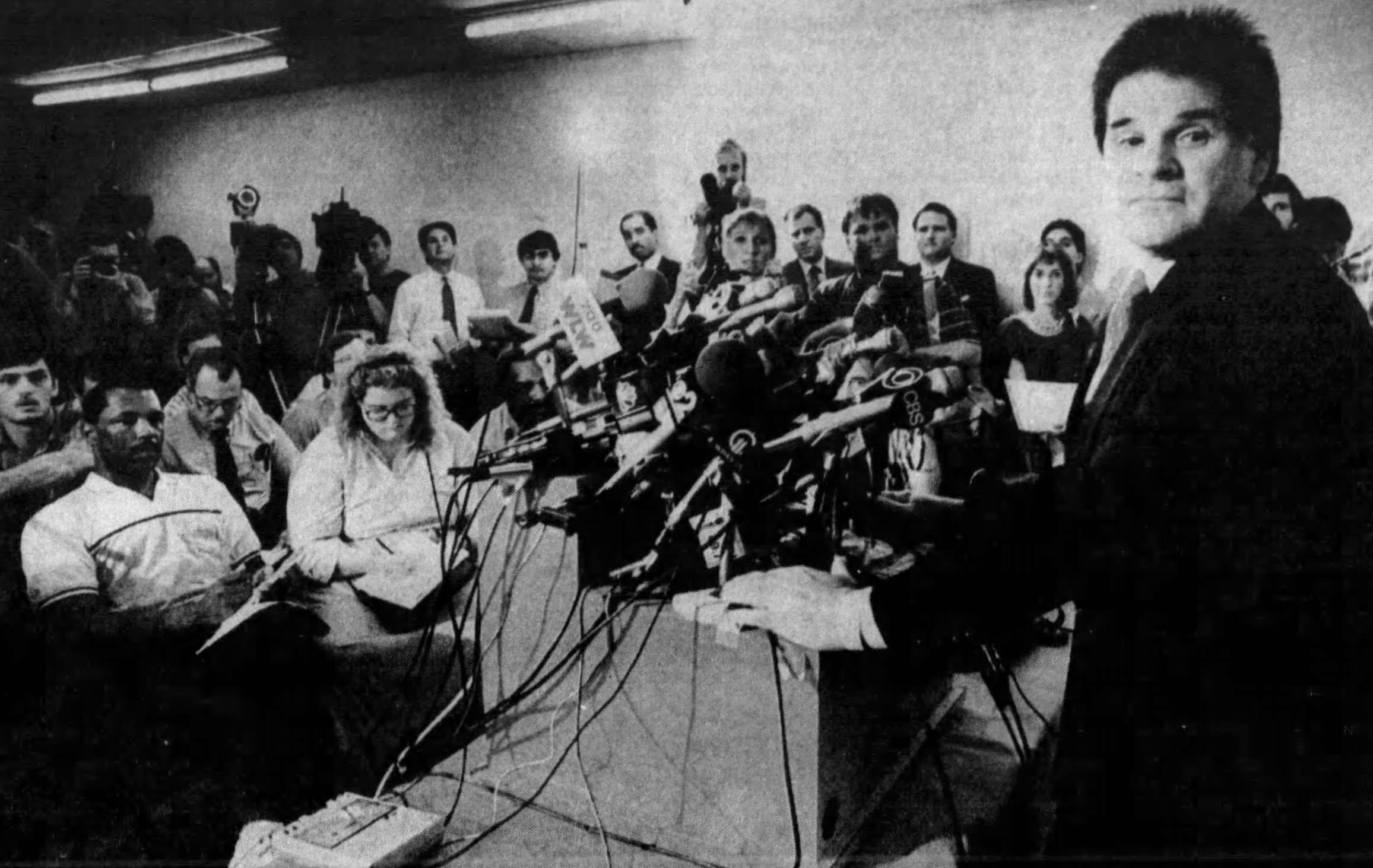

“It’s my belief that over a quarter of a million dollars was paid for the evidence that was crucial to the successful investigation,” said Baker in 1987 when he headed his department’s internal investigation of police wrongdoing. “Our investigation disclosed that the crucial tape recordings were removed from the Police Department and sold to one of the defendants in the case.”

The informant told the Dayton Daily News that she made the payment while she was working as an informant for the FBI. The evidence consisted of taped phone conservations of the informant allegedly making a drug deal.

Baker said he and Lopez’s investigation of the case was hampered when FBI agents refused to cooperate. Lopez, who was investigating allegations of police wrongdoing and the apparently groundless dismissal of criminal cases, said he referred the case to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Lopez told the Dayton Daily News in 1987 he would have continued to pursue the case if it hadn’t been for “a federal presence.”

Asked what he meant, Lopez said “Baker hit a brick wall” when he sought the FBI’s permission to interview the informant about the case.

“Mr. Lopez is correct,” Baker said of his investigation. “When I took my information to the FBI, they were reluctant to cooperate with my efforts to interview her and review any evidence that may have been in their possession that may pertain to their investigation.”

The case against the FBI informant began in 1981 when she was indicted by a Montgomery County grand jury on one count of conspiracy to commit aggravated trafficking of cocaine and methaqualone. During the three-year period following her arrest, she was never taken into custody despite outstanding warrants for her arrest.

On Dec. 22, 1983, her case was dismissed by former Montgomery County Judge W. Erwin Kilpatrick at the request of Assistant Montgomery County Prosecutor James Cole. But the case was assigned to Judge John M. Meagher, who said he was never notified about the dismissal.

Cole said the prosecutor’s file in the case disappeared. He also noted Dayton police asked for the case to be dismissed.

“It is strange that it (the file) disappeared,” Cole conceded. “Usually, you can track them down.” He did, however, produce a brief notation about the case that read, “Dismissed. Request of police. Snitch.”

Court records confirm the informant’s work as a “reliable” FBI informant for the three years preceding the 1984 search of Stepp’s home, and attest to her assistance in other FBI investigations. Among the items the FBI lost following the raid were cassette tapes the FBI believed contained conservations between the informant and FBI agents that former FBI Special Agent Robert A. Brawner said in a sworn statement would have proved “the existence of a wire-intercept violation against Bill Stepp.”

Protected

Haller said Stepp’s charmed life wasn’t the only reason he was convinced Stepp was an informant.

Haller recalled Stepp parking “this beautiful Mercedes” at a restaurant where he was dining “and he comes in and asks me how I’m doing ... and I look at his wrist and he’s got this Rolex watch that’s totally dressed out in diamonds. And I say, man, that’s one hell of a watch and he says, ‘Yeah, 50 grand worth.’ And I look down on his finger and he’s got a four-carat diamond on it.”

“So what kind of guy wears a $50,000 watch and a four-carat diamond ring?” Haller asked. “The answer is someone who’s protected.”

Asked how he was able to get Stepp to talk to him, Haller noted he once had “a little heated talk” with Stepp “and I told him — ‘If I blow your (expletive) brains out, you know, I’ll be a hero. Don’t you (expletive) with me!’ So, anyway, Bill and I always got along after that.”

Stepp died of natural causes at the age of 73.

Staff Writer Greg Lynch contributed to this report.

GEM CITY GAMBLE

A project from the Dayton Daily News

Former Dayton police Detective Dennis Haller’s career spanned a dark time for the Dayton Police Department. Haller was a source for Dayton Daily News reporter Wes Hills, who retired in 2004 after 30 years at the paper, and agreed to share information with Hills on the condition it stay confidential until Haller’s death, which happened in 2023.

Now, we bring you Gem City Gamble, a series that uses Hills’ interviews and notes to shed new light on the largest police corruption scandal in city history and how police wiretapping and a spurned bookie may have contributed to the downfall of baseball legend Pete Rose.

About the Author