One factor in “how we got here,” not covered enough by the national news media, is the disappearance of local news. Northwestern University’s Local News Initiative tracks news deserts: “areas that lack consistent local reporting that fills information needs.” The U.S. now has 206 counties without any news source and 1,560 counties (out of 3,144) with only one source.

Northwestern’s study looked at 193 of those counties and found Trump won 91% of them over Harris. Although his margin of victory in the popular vote was a slim 1.5%, Trump won news desert counties by an average of 54%.

When we have little access to local information, we gravitate to talk radio, cable chatter and social media. So instead of looking inward to our communities, we look away, searching for opinions across the national media that affirm our existing beliefs.

We know from research that when towns lack local news, community involvement and voting turnout decline. In Oxford, anecdotal evidence offers some good news about the return of a weekly newspaper. Our editor’s sources have seen an increase in awareness around housing issues; local social service agencies have received more individual donations; the library reports patrons stopping in just to pick up copies of the paper; and news coverage of a Fire/EMS levy laid out the stakes to voters and passed with almost 73% support, the widest margin ever for a county levy here in a November election.

Two studies demonstrate that access to local news lessens polarization by refocusing communities on issues that affect our everyday lives, issues that we can do something about.

Danny Hayes, a political science professor at George Washington University, is co-author of “News Hole: The Demise of Local Journalism and Political Engagement.” In an email to me, he called local journalism “a defense against polarization.” Studies have shown, Hayes noted, that Americans with access to quality local news are less partisan and more likely to be split-ticket voters.

“Polarization is a tough problem to solve,” Hayes told me, “but local news seems to be one of the few things in the world that can bring people together rather than drive them apart.”

Joshua Darr, a public communication professor at Syracuse, is the lead author of “Home Style Opinion: How Local News Newspapers Can Slow Polarization.” The book examines a California newspaper that dropped a national news focus from its opinion page, rebooting the page with local writers addressing local issues. The study showed that a newspaper, by downsizing national political opinion-makers, pushed back against polarization: ”politically engaged people did not feel as far apart from members of the opposing party.”

So what else can be done about our partisan divide? First, the national media need to treat the loss of local news as a national crisis, not a scattered problem here and there. Second, journalists should not rely solely on sources from left and right extremes, which certainly generates the most drama and conflict … and perpetuates the false notion that some kind of balance has been achieved.

Locally, we need to support local news. Currently, laws or initiatives in 13 different states address the local news crisis. Since the internet destroyed the classified ad business, the more than 250 news start-ups today are mostly online and nonprofit. They need our support.

It is through journalism that we learn about what’s going on in our town, state, nation, and world. Our current president once called the press an “enemy of the people.” But let’s remember that “the press” was the only business our founders singled out for protection in our Constitution. They understood that for democracy to work, it needed a free press.

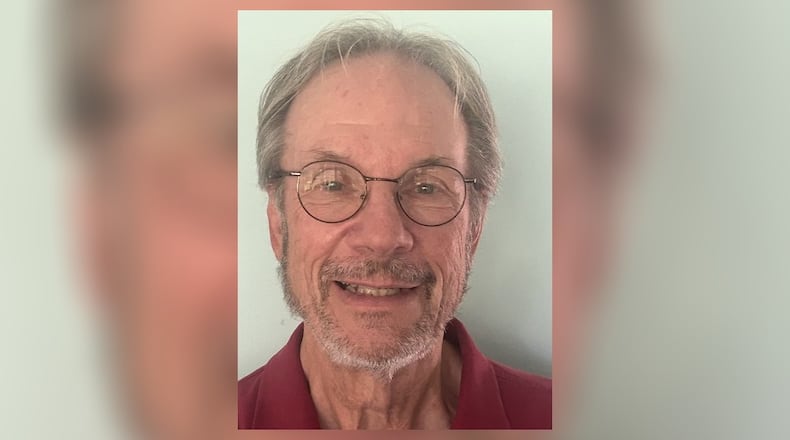

Richard Campbell is co-founder of the nonprofit Oxford Free Press and professor emeritus at Miami University. A version of this column appeared earlier in the Oxford Free Press.

About the Author