So DeMora (D-Columbus) is thinking through a bill to bring more fairness to bourbon buying while reducing reselling and profiteering.

DeMora introduced Senate Bill 320 on October 31, but it won’t advance since this year’s legislative session is nearly complete. DeMora can now take time to talk to people about the bill, which he plans to reintroduce next year.

“I want suggestions on how to make this a better bill,” DeMora said in a phone interview. “But in the end, I’m trying to level the playing field for everybody in Ohio to get the stuff that’s most coveted.”

The bourbon market is as hot as the sun’s core, and enthusiasts go to amazing lengths to purchase a rare bottle. The Ohio Liquor Control Board holds raffles for these “allocated” bourbons, which include brands such as Pappy Van Winkle, Williams LaRue Weller, and George T. Stagg, to name a few.

People will often wait in line, overnight, hoping to get a prized bourbon from stores with only a handful for sale.

But it’s what happens next that DeMora, himself a bourbon fan, really wants to stop.

“Flippers” buy bottles so they can resell them at many times retail — an illegal practice that’s tough to stop. For example, the rare Pappy Van Winkle 23-year-old retails in Ohio for $449.97 but fetches 10 times that on the resale (called secondary) market.

He said the products “just bought end up on the secondary market within hours. It prevents regular people from getting this stuff.”

DeMora’s bill would require anyone buying an allocated bottle to open the cap and then reseal it in the store. Flippers generally can’t resell expensive bourbon once opened buyers can’t trust what’s in the bottle.

Moreover, DeMora would like to limit the number of allocated brands a buyer can purchase every 30 days. So if you buy a George T. Stagg, you won’t be able to get a second bottle from another store. Purchases would be tracked via driver’s license.

The proposal would only impact allocated products, not the bourbons readily available on the store’s shelves like Wild Turkey, Evan Williams, and Jim Beam.

DeMora has to figure out how not to hurt charitable organizations that raffle bourbons, and a mechanism for cutting down or eliminating overnight lines with dozens of people, sometimes more.

Bourbon distribution fairness has been on the state’s radar for years because distilleries dislike flipping as much as the average bourbon buyer. Companies want a range of people to try their products so they can expand their customer base. Flipping puts the bourbon in the hands of those who can afford vastly inflated products.

I used to be one of the “line people” who would wait for hours — and drive hours — to buy one bottle of bourbon I just had to have. I stopped when I realized the allocated products were more about status and prestige and less about taste. There’s a lot of excellent bourbon for sale.

DeMora’s biggest challenge might be ensuring buyers don’t get advanced notice of certain sales. He could require state stores to vary release days and times and institute penalties for tipping off customers. He could set up allocated-only receipts that serve as an affidavit that the bourbon is for personal consumption only. Varying release times could cut down on lines since no one would know how long they must wait.

Most bourbon buyers will cheer this effort while the flippers will despise them. Realistically, there’s no way to stop individual groups from selling bourbon at a minimal markup or trading for similar products.

But there may be a way to put a dent in the flipping market, which would put more hard-to-get bourbon into more hands.

Here’s hoping it works.

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday. He collects bourbon, publishes the monthly Bourbon Resource, and is president of the 32 Staves Society.

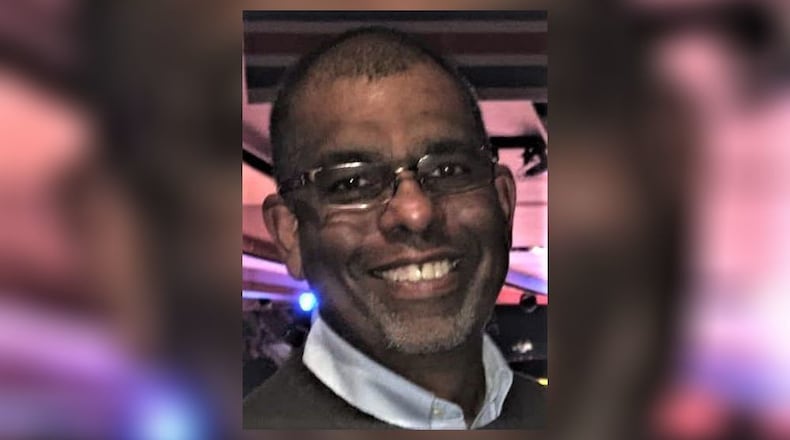

About the Author