The legislation goes to the Senate, which should remove the bond provisions.

Just say no.

Ohio shouldn’t use taxpayer money to help construct a new playpen for billionaires and their players.

When a state sells bonds, investors buy them expecting a set return over a specific period. In the case of the Browns, Ohio plans to use tax revenue derived from the stadium and a proposed mixed-use development to cover the bonds’ cost.

There’s so much wrong here.

Browns owners Jimmy and Dee Haslem say they’ll put up $1.2B while Cuyahoga County and the state will each contribute $600B.

How does this make sense for taxpayers?

The Haslems have a combined net worth of about $8 billion, according to Pro Football Network. The Browns, as a team, are worth $5.15B, according to Forbes.

Moreover, the Browns had the top payroll in the NFL last year, at $246.4 million. The franchise just made the defensive end Myles Garrett the highest-paid non-quarterback in NFL history ($40M per year). I know the salary bucket is different from the construction budget, but the point remains — the Browns have the money.

Research shows that most publicly funded sports ventures don’t lead to economic booms in the immediate area. “NFL stadiums do not generate significant local economic growth,” the Stanford University economist Roger Noll told the Stanford Report, the institution’s news service.

The Browns disagree. The team says the new stadium it wants to build 15 miles southwest of Cleveland in Brook Park would generate “an annual direct economic output of $1.2 billion across Cuyahoga County, as well as create nearly 5,400 permanent jobs.” But those numbers are based on assumptions, including that 1.5 million people will annually attend events at the new stadium.

When you’re playing with public money, never assume.

The financing plan already faces headwinds. Governor Mike DeWine said using state bonds is “not the way to go” and noted the final cost could soar past $1 billion when accounting for additional interest.

Attorney General Dave Yost, who’s running for governor, came out against the deal in a Columbus Dispatch opinion piece. Cleveland officials are livid that the Browns want to leave a city that primarily funded its existing stadium.

The bonds are supposed to be repaid with tax revenue from the new development, but if revenues fall short, the state — taxpayers — have to make up the difference.

This one is rich. The Cincinnati Bengals want $350 million in state dollars for improvements to their stadium. So in the midst of the Browns’ funding row, the Bengals have coyly threatened to move the team if it doesn’t get what it wants. The team’s lease at Paycor stadium expires June 30, 2026, as the Bengals should get the same message — pay your own way.

Professional teams have traditionally put cities and states in a bind because of the strong emotional bond with their clubs. It’s prestigious to be called a major-league city. There’s free advertising and marketing when these teams appear on national television. I don’t know the numbers, but you would think there’s an impact when an announcer notes Cleveland is the home to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Research quantifies the overall impact, and it shows these projects don’t produce the revenue often projected.

That’s why we need to stop the insanity.

Don’t use tax dollars to prop up professional sports teams.

And if they threaten to leave?

Wish them well. We can stream the games.

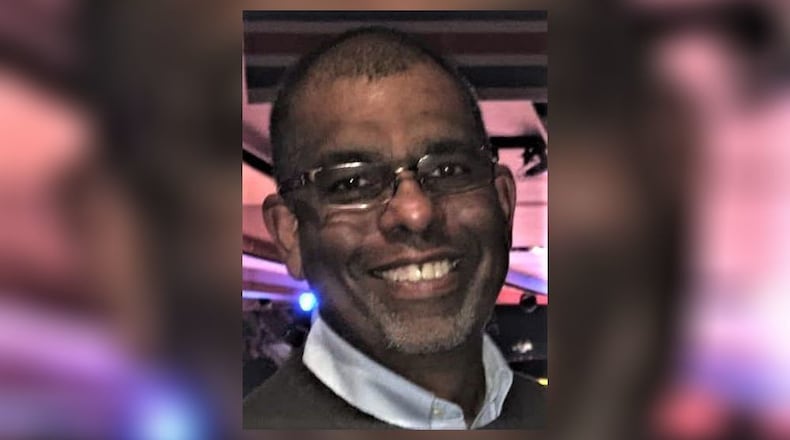

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday.

About the Author