This issue will be Issue 1 on the November ballot and is the only statewide issue before voters this election.

Here’s what you need to know about Issue 1.

How would maps be drawn?

Here are the specific rules under Issue 1:

• All maps must comply with United States Constitution, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and all other applicable federal laws.

• Partisan gerrymandering is banned, as is “the use of redistricting plans that favor one political party and disfavor others.”

• Commissioners must also “comply, to the extent possible,” with the following rules: Like districts must have relatively similar populations; districts must “ensure the equal functional ability of politically cohesive and geographically proximate racial, ethnic, and language minorities to participate in the political process and to elect candidates of choice;” and districts need to preserve communities of interest to the extent practicable.

• On proportionality, Issue 1 says: “The statewide proportion of districts in each redistricting plan that favors each political party shall correspond closely to the statewide partisan preferences of the voters of Ohio.” The amendment would allow deviation up to 3%, but notes that in cases where 3% and under is impossible, commissioners must pick the map with the smallest difference.

How is this different from now?

The actual process and guidelines for drawing legislative maps under Issue 1 are similar to the current system.

One notable exception is that Issue 1 would say maps should be drawn with no consideration of where the incumbents in those district live, unlike the current rules that prohibit drawing an incumbent out of their district.

Both the current system and Issue 1 place an emphasis on proportionality. The current system looks at voting data over the past 10 years to roughly determine Ohioans’ partisan leanings. Issue 1 would look at the past six years. While the current system requires that the sum of the maps “correspond(s) closely” with the partisan lean of the state, Issue 1 defines that the maps should be within 3%, if possible.

Both systems require districts to be contiguous and both require map drawers to consider communities of interest.

Who would draw the maps?

This is the biggest difference from the current system.

Under the current system, seven politicians — the governor, the auditor, the secretary of state, two Democrats and two Republicans from the legislature — are granted the power of the pen. This system has been called into action twice, each time having a partisan lean of five Republicans and two Democrats, and consensus has been hard to come by.

Issue 1 would dissolve that panel and replace it with a 15-member citizen commission meant to be free from political imbalance and personal stakes. The commission would consist of five Republicans, five Democrats and five voters not affiliated with either major party.

How would the new map drawers be picked?

One of the most common questions about the proposal is how the 15-member commission would be selected. It’s a complicated process.

First, two members from each party on the Ohio Ballot Board would each select two retired judges, creating a four member “bipartisan screening panel.”

That panel would field applications from Ohioans interested in becoming commissioners.

The four-judge panel would narrow down applications to a list of 90 qualified people — 30 Republicans, 30 Democrats and 30 others (which could theoretically consist of green party voters, libertarians or other third parties) — which would be made public. Those individuals would then be vetted by an outside contractor and interviewed, with the interviews being made public.

With help from public input, the screening panel would then whittle the list down to 45 finalists, 15 from each ideological pool and all from a “geographically and demographically representative cross-section of Ohio.”

Soon thereafter, the panel would randomly draw two Republicans, two Democrats and two from neither major party to serve as commissioners. Those six commissioners would then select nine individuals from the remaining pool of finalists to fill out the 15 member board.

What are the qualifications?

Commissioners must be registered voters who are residents of Ohio and lived continuously in Ohio during the current year and the previously six years.

The proposal says commissioners could not have any employment or contracts or “other involvement” with elected officials or candidates for office, or any contractual relationships or involvement with political parties, ballot measure campaigns, or political action committees.

This prohibition extends through the prior six years.

Public employees such as teachers, public university professors or police officers would not be exempt from participating due to their occupation alone.

Are they paid?

Commissioners are paid $125 per day they perform work on behalf of the commission, plus reimbursement for travel expenses.

How often would they meet?

The first rule regarding the commission, if passed, is the timeline. Issue 1 says says the panel must start in 2025 to create maps for the 2026 primary election. After that, the commission would be convened once following each publication of the U.S. Census, which occurs at the start of every decade.

Approved maps would be good for the remainder of that decade, under the plan. Approval of any map would require an affirmative vote of at least nine members, including at least two members from each ideological pool, theoretically preventing one party from steamrolling the others.

The citizen panel would be required to hold at least 10 meetings across the state throughout the process, with two meetings each occurring in southwest Ohio, southeast Ohio, northeast Ohio, northwest Ohio and central Ohio — an idea similar to the current process, but considerably more fleshed out.

Can members get kicked off the commission?

According to the proposal, commission members can only be removed from the commission by their peers. A vote for removal must be preceded by a notice, a public hearing, and an opportunity for the public to weigh in.

Causes for removal include: Failure to disclose relevant information about themselves; willful disregard for the proposal’s map drawing rules; wanton and willful neglect of duty; incapacity or inability to perform their duties; and “behavior involving moral turpitude or other acts that undermine the public’s trust.”

Who would pay for the commission?

Under Issue 1, the commission would be paid for by public tax dollars, as is the current commission. Issue 1 requires $7 million for the 2025 redistricting cycle, which Issue 1 backers say is the same amount of money spent by the current redistricting commission for the 2020 redistricting cycle.

Other notable costs involve the contracting of private search and screening firms, legal experts and litigation, if called for.

Who supports Issue 1?

Issue 1 is backed by a campaign called Citizens Not Politicians. The face of the campaign is Republican former Ohio Supreme Court Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor.

The campaign bills itself as nonpartisan, though it has significant support from Democrat and progressive groups who accuse Republicans who control the current process of putting their thumbs on the scales to benefit their party.

Early campaign finance reports show that 84.3% of the more than $23 million raised by Citizens Not Politicians came from out-of-state donors. The overwhelming majority of those funds have come from progressive dark money groups, such as the Sixteen Thirty Fund, which has drawn consternation from Republican opponents.

Issue 1 backers note the courts repeatedly rejected the maps produced by the current GOP-dominated redistricting commission as gerrymandered on partisan grounds.

“It is an innate conflict of interest. They can’t help themselves,” said O’Connor to a crowd of about 170 people at the Dayton Metro Library in August. “Whether they’re Ds or Rs, they can’t help themselves to retain power, to expand power, to do what is best for party over citizens, and that’s exactly what we’ve seen.”

Who opposes Issue 1?

An Issue 1 opposition campaign has formed by the PAC Ohio Works. Ohio Works has not yet had to disclose its donors.

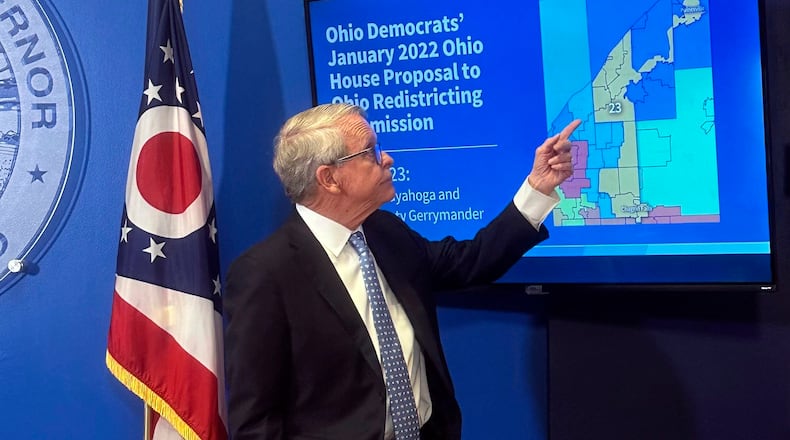

Other vocal opponents include Republican elected state officials — such as Gov. Mike DeWine — and some trade and business groups.

Issue 1 opponents attack the proposal saying the proposed commission lacks accountability, and that the proportionality requirement bakes gerrymandering into the system.

“Issue 1 is a Democrat power grab that will cost taxpayers million and take away their input,” Ohio Works says on their website. “Out-of-state special interests want to create a commission that will have virtually unlimited power to spend Ohio tax dollars — with zero accountability to Ohio voters.”

About the Author